The Costs of Defence - Analysis of the NAO Report into the MOD Civil Service

When it comes to discussing how to save money in the Defence

budget, one of the most common themes emerging on comment sections of newspaper

websites is the refrain ‘sack all the civil servants who just sit behind desks’

or words to that effect.

These comments are usually accompanied by tired clichés like

‘the SA80 is known as the Civil Servant – it doesn’t work and cant’ be fired’ and

how they have no idea what it is like on the front line and our poor soldiers

have boots that don’t fit while fat cat civil servants get bonuses. Attacking the MOD Civil Service is an easy win

– few people stand up for them, few people like civil servants and frankly

anyone who dares work for defence without wearing uniform is probably suspect?

There is a completely false public perception that during a

time of large manpower reductions to the regular military, the Civil Service

has gotten way without suffering the same pain. According to self-proclaimed

experts, a large cull of these wastes of space would solve every military

problem known to man (except whether to have your sleeves rolled up or down and

whether jackets are tucked in or out).

The 2015 SDSR made clear that the Civil Service was to be heavily

cut in order to meet financial savings targets, while the regular military

headcount was to be preserved at any cost. This move sat well with commentators

who were pleased at the prospect of seeing nearly 15,000 civil servants lose

their jobs by 2020.

On 8 March the National

Audit Office produced a report into progress to date in meeting these targets,

and whether the MOD will hit the goal of having approximately 40,000 civil servants

by 2020. The results are challenging and potentially difficult reading for those

who take a long term view about defence.

The key fact emerging from the report is that the MOD does

not think it can meet the requirement to cut 30% of its headcount, but that it

can find equivalent savings from the wider civilian pay bill.

To all intents and purposes one of the key outcomes of the

2015 SDSR has been scrapped and replaced with a very different goal of finding

savings without finding the same level of headcount reductions. This is a very

welcome decision, that the report identifies has been reached for several

different reasons.

Firstly, the challenge for the MOD in cutting headcount is

working out what to cut and where to cut it. The 2015 SDSR began the process of

reducing numbers by some large scale moves, such as reducing the number of

locally employed civilians in Germany (where some 4,000 local civil servants

were made redundant), to privatising or transferring departmental functions to

other areas (for instance the Met Office now sits under BEIS).

But the problem strikes when you then try to work out how

you can continue to cut and where to do so. As the report notes, MOD staff are

spread across 570 different sites, and more than 50% of staff (roughly 25,000

people) work in over 300 small sites

with no more than 10staff present.

This diaspora is widely dispersed across the country (as the

image below shows) and represent the hugely diverse range of areas where the

MOD runs facilities. To meet the sort of headcount reductions demanded would be

very difficult without closing these sites en masse.

|

| MOD Locations in the UK |

This would have a deeply damaging impact on defence and

local economies- often Defence is a

major employer for a region (for instance RNAS Culdrose is one of the single

biggest employers in Cornwall), and site closure will have wider economic

ramifications.

The work done by locals on these sites is not nugatory – it is

often intended to do things like guard duties (ensuring security), or local administration

to support regular military units (ensuring people are paid, equipped and

properly supported) or delivery of training (e.g. range safety wardens) or all

manner of other small discrete tasks.

If you remove these people from the site, the need to do the

work doesn’t go away – it merely gets passed somewhere else. Consequently it

has proven extremely difficult to work out what can be done to reduce headcount

across over 300 sites because the reduction would have a disproportionate impact

on output.

The wider problem is working out what roles to cut without

hurting Defence as a whole. Contrary to badly informed public opinion, the role

of the MOD Civil Service is not to function as generic ‘admin officials’ but to

work across a very broad range of skills and areas.

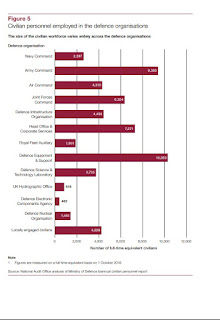

The table below, also taken from the report highlights just

how diverse these responsibilities are, and how critical they are. For example

one of the largest parts of the MOD Civil Service is the defence engineering and

science function -without which the ability of the armed forces to operate globally

would rapidly grind to a halt.

|

| Career Areas for MOD Civil Servants |

These assets are also spread across the complex mixture of

organisational boundaries that make up Defence – for example nearly 23,000

Civil Servants work in Front Line Commands doing very different work. There is

not a homogenous group of individuals doing nearly identical work and outputs

that can be merged to be more efficient. The role of a junior admin assistant in

a barracks near Inverness is utterly different to the work of a project manager

working in Navy Command in Portsmouth. The scope to rationalise the workforce

is very difficult without directly harming outputs.

A further challenge is that of retention and demographics.

The Report pulls no punches in noting that across the MOD there are no less

than 57 ‘pinch points’ for civilian staff at the moment. A pinch point is an area of critical shortage which could

have major impact on the ability of Defence to deliver. This is not about a shortage

of paperclip counters, but a real shortage of staff with skills that take

decades to acquire – for example at the moment there is a shortfall of 1,650 staff

in areas such as nuclear engineering, finance and also programme management.

While these areas may perhaps lack the glamour of the

military pinch points like special forces operators, pilots or Principal

Warfare Officers, they are still a vital part of ensuring UK security. A

failure to secure sufficient nuclear engineers calls into question the long

term viability of the nuclear deterrent and submarine force -one of the most central

planks of UK security policy.

These pinch points are coming about for a variety of

reasons, but one of the most challenging parts of the review to read is the

looming demographic timebomb facing the Department. The report notes that today

roughly 55,000 people work for the MOD, of whom 47% are aged over 50 (up from

41% in 2010). By contrast just 11% of the workforce are aged 16-29.

At the same time though the MOD is losing proportionately more

16-29yr olds than it is over 50s. A recent survey showed that in 2018 12% of the

16-29 year old bracket left the MOD, compared to just 5% of staff in the 30-59

bracket.

The MOD therefore has the double problem of a rapidly aging

workforce, while being unable to recruit and retain a younger generation to

replace them. This raises serious questions about the long term sustainability

of skills and knowledge given that there seems to be no coherent long term management

plan to replace them.

In previous years staff had their careers closely controlled

by HR, who would move them into posts at an appropriate point to help fill

roles and ensure skills were developed. Someone entering as a junior

intelligence analyst (for example) could expect to be moved regularly within their

world and develop as a deeply specialised analyst over 20-30 years.

By contrast the modern system based on ‘core competences’ gives

staff the freedom to move where they wish, but removes any ability for central

HR planning to fill core roles or develop cadres of specialists. This makes it

harder for the workforce planners to know where they can get qualified staff

from to fill gaps (a major issue for more niche or senior roles).

At the same time staff are leaving due to poor pay and

conditions. While more senior staff benefit from significantly better pensions

(a likely reason why so many over 50s have remained, knowing they are on the protected

final salary pension), new entrants have suffered with the combination of a new

less attractive pension based on career average salary at a point when public

sector salaries have been frozen in real terms for years.

Humphrey has met civil servants who due to the combination

of tax and NI rises and pension contribution changes combined with a 1% pay rise

ceiling are now taking home less net per month than they were in 2010. This is

not conducive to feeling like you are a valued part of the organisation.

It is no wonder then that the MOD is struggling to retain

staff – barely 20% of MOD staff feel their pay is adequate, and the report

notes that recently 75% of electrical apprentices left immediately after completing

their apprenticeship primarily due to the poor pay on offer compared to other

employers.

At the same time the significant changes in terms of service

meaning it is almost impossible to move around the MOD beyond your local area

make it hard for civilians to move and develop. Years ago people had excess

fares and relocation expenses paid for. Today, outside of a tiny number of roles

it is impossible to secure this – someone in Liverpool wanting to broaden and

move to a new promotion role in Bristol or London and thus stay longer and

solve the skills gap has to self fund the entire relocation themselves – this

is practically impossible for many junior CS, and is a major reason for the

near total collapse of social mobility and staff moves within the MOD – this may

have far reaching consequences.

|

| Staff broken down by Budget Area |

The MOD therefore is in an almost impossible position. Its

workforce is aging, feels it is underpaid and the people it needs to keep and

retain for the long haul to be the next generation of leaders, scientists and

engineers are not staying. The view seems to be that why show life long loyalty

to a system that seems determined to ruthlessly cull numbers?

But, the solution to increasing retention (e.g. better pay

and conditions) seems outside the ability of the MOD to deliver – it has to

find over £300m in savings from the civilian pay bill (which is approximately

£2.5bn per year) without being able to reduce staff due to the damage this will

have on Defence outputs.

The challenge for planners is trying to find the combination

of financial headroom to meet these targets and find spare cash to retain

people. Part of this may come about from better defining elements of the

Departments work – for instance more clearly understanding where scope may exist

for rationalisation of sites or roles – but this is linked to wider decisions

such as the Defence Estate Strategy – when the decision is taken not to close

somewhere, this reduces the ability to cut these posts.

Alternatively future military headcount reductions, such as

the long rumoured cut to the Army from 82,000 to 60-65,000 will result in significant

freeing up of sites to close, and units to disband. This will free up a lot of local

civil servant headcount for reducing manpower overall and savings.

The MOD has to think carefully about this and more widely about

how it works to make best use of its management of information to understand

what it wants its civilian workforce to do, and how they can be best managed to

do this. It also has to decide how to balance off the twin challenges of cutting

civilian manpower while also using civilians as a very attractive substitute

for more expensive military manpower in many posts – this doesn’t necessarily

drive coherent planning or behaviours.

Standing up for the MOD Civil Service is not a popular thing

to do. Internet hardmen think that the Civil Service is a scandalous waste of

public money, and don’t hold back from saying so. Humphrey has lost count of

the abusive messages, comments and emails he has had for saying that the MOD has

an amazing workforce full of brilliant people who deserve a damn sight more

respect for the work that they do to keep this country safe.

The Mod has got really difficult decisions ahead of it, but these

need to be made now to prevent problems in 15 years time. Based on the current

evidence, unless major change is made to how recruiting and retention is handled,

and how skills and knowledge are transferred in a coherent manner, the UK is at

real risk of losing priceless hard won experience as half the MOD workforce retire,

without any coherent ‘one for one’ replacement plan in place.

Just to stand still and keep MOD staff levels as they are is

going to require a significant increase in recruiting now to generate staff

with the right experience in 5,10, 15 years to replace todays officials. Unless

major and likely politically unpopular changes are made to improve the offer,

address pay and provide a platform where people want to join and stay, and not

leave for industry, then it is no exaggeration to say that there would be

exceptionally serious consequences for the security of the nation. We need as a country to recognise that MOD

Civilians are the ‘Fourth Service’ and treat them with the respect and

appreciation that they so richly deserve.

pinstripedline@gmail.com

There are "recruitment" (we call it a "job advert") happening all the time for DE&S. You only have to follow their twitter of FB paged

ReplyDeleteDE&S are recruiting all the time because staff retention is abysmal. The numbers for the last year are staggering. People are leaving in droves, for all the reasons Sir H mentions.

DeleteI read the NAO report and really recommend others read it too. NAO are a jewel in the crown of UK government. A good auditor is worth their weight in gold and who ever wrote this report is great at putting messages into simple English, a skill which is much underated.

ReplyDeleteMy observations;

The MOD is broken when it comes keeping to commitments. It is so bad you have to think about whether it can ever be fixed or drastic surgery is required. In most organisations if an audit identifies a problem and they come back years later and it is still there the management get reprimanded, here NAO is calling out the same problem time and again, with no improvement being shown, yet careers progress. If a senior leadership can't get a plan together to resolve a problem, then they are the problem.

The MOD civil service is hugely southern England biased. I will speculate that the reason that there's a problem with retention of the younger age groups is that if you are in that age group you need to move to a job which pays you enough to afford a place to buy. That's unlikely to be the MOD. Despite the concentration in the south, there are still multiple big sites, which raises the question of why is the MoD failing to consolidate and merge support operations.

The comment Sir H makes about lack of technical resources can't be backed up because the MOD managers themselves say the data on employee skills is unreliable. If you don't have confidence in the basic data then all conclusions after that are suspect. Again, the MOD has to be taken to task about why the basics aren't been done right.

Don't forget how it started.

ReplyDelete"Its previous headcount reductions were made in an arbitrary way in order to achieve savings targets that had been imposed to allow for spending elsewhere (for example, on the Equipment Plan)."

That was over 23,000 staff (God knows how many years of experience)

VERS (2011-14) principally made financial sense for 50+ people although I did know some people who left on VERS and then joined one of the private firms providing services to the MoD a few months later.

ReplyDeleteAlas, reform is impossible within a system that moves the vast majority of its senior leadership cadre every 2-3 years (or a lot less if they are going places). No one ever has to live with the consequences of their decisions and any attempt at change has a rather short half life. The current system is therefore simply unable to fix itself. If you suggested that any other sector rotated all their senior staff as a matter of principle they would look at you as though you were mad....

ReplyDeleteThe MOD is in trouble, trying to recruit engineers and scientists, when folk start leaving the payroll to be contractors instead (because the choice is pay contract rates, or do without)

ReplyDeleteThe MOD is in real trouble when contractors are leaving it to work in industry, and are earning more as permanent staff there than as contractors for MOD...